Many of my friends believe I am an expert in fine-art photography. I am not.

If I print out the 15 thousand photos on my phone, frame them, put them into a show, and pay people to go and see it with the promise of a bonus if they make it to the end – it would be a massively tiresome embarrassment. It wouldn’t be an art show. It would be torture. This imaginary experiment doesn’t define when and how photography becomes art; it simply demonstrates that not all photographs belong to the realm of fine-art photography.

But what is art photography? In 1853, at the first meeting of the Photographic Society in London, photography was proclaimed art if it resembled a good painting. This definition has been changing ever since, every ten or twenty years, and today’s repository of all knowledge and ignorance – Wikipedia – defines it as “photography created in line with the vision of the photographer as artist, using photography as a medium for creative expression” and considers it separately from photojournalism.

Alas, this definition is the vaguest of them all. It can be applied to virtually any image with equal success. If I think of myself as an artist (actually, I don’t) and have a vision (actually, I do), use my phone’s camera as my tool, and proclaim the photo I’ve just taken my “creative expression”, that photo becomes fine-art photography.

And…crushing back to reality – it doesn’t happen. That “fine-art” photo would soon get lost among the 15 K images that are already on my phone and die peacefully when I buy a new phone model.

So, instead of defining the universe of fine-art photography in one go, I prefer to classify it first and then get myself guided by the lighthouses of examples within simplified categories. And I use examples that – at least for me – are good representations of artistic expression.

This approach helps me a lot to navigate the world of photography.

Just as Wikipedia does, I also relegate photojournalism to a category of its own. This might create a problem for an art theorist, but for me, it is simple: there’s breeding, and then there’s hunting, and these two activities are very different, even though the end result may be more or less the same. Hunter-photographers may end up with an epoch-defining photograph like Alfred Eisenstaedt’s V-J Day in Times Square, and these photographs become objects of art, but I will not be talking about journalism or street photography this time.

The first step in my “simplification” of fine-art photography is mechanically formal.

I broadly divide photographs into staged or unstaged. The staged ones can be further divided into “presented as unstaged” and “presented as staged”.

This simplification is not actually that simple. The boundary between staged and unstaged photos is blurred. Even in a landscape photo, photographers choose the time of day, the lighting, and the composition – in short, they try to create the best presentation of randomness.

UNSTAGED: WHERE IS ART IN THAT?

Well, here are a couple of example lighthouses.

John Pepper waited hours to get this photograph of a dune, flattening himself on a mattress that still failed to prevent elbow and knee burns in Iran’s hottest desert.

George Tatge believes that each object (or a set of them) has the ideal moment in the timeline of its existence at which it can be photographed and finds himself in luck when the trajectory of his life intersects with that of the object, thus creating the perfect opportunity to immortalise it in a photograph.

GEORGE TATGE – ARCHITECTURE

Piazza Capranica, Rome (2007)

Both photos are great. Not because they “capture a nice moment in time” but because they are metaphors for much more than what is shown. Pepper’s dune talks about stability and dynamism through just a single shape, like the yin and yang of life itself, of the tension between light and shadow, of the world’s perfection and simplicity that we crave but can rarely experience. Tadge’s photo – “flatness squared” as it is a flat image that shows a flat wall – is a conversation starter for the discussion of catholic influence in modern Italy. Many would say the once powerful Church is today nominal and waning, but the Catholic mindset still casts a vast shadow on the Italian subconscious.

The truth is, a great unstaged photo is more than just seriously rare. It is scarce, even in the oeuvre of very talented photographers.

STAGED AND PRESENTED AS STAGED

That category fits Wikipedia’s definition of fine-art photography like a hand into a custom-tailored glove. A lot of effort and production budget goes into staging, so artistic intention becomes quite visible, especially if the photographer has to trouble themselves with filling out tax forms at year-end.

Most fine-art photography is staged, almost “written” as a novel or a play, and then directed and captured. Alas, most of it ends up becoming pulp fiction with a moth’s lifespan. A great staged photo is as rare as Nobel prize-quality literature.

Plus, it is risky.

Unlike in unstaged photography, where people would usually dismiss an image by saying, “No, that was not a good take”, in this category, once you’ve spent time and money on staging, you make the loud announcement, “This is the work of a professional artist”. To that, viewers do not say, “It is a failed photo”. They say, “It is a failed artist.” So, the risk of being shot down at a career launch is towering. But the reward is similar to that of a professional writer. Once a “staged-photo” photographer survives one or two exhibitions, he becomes acknowledged as a pro whose failed project means just that, a failed project of an otherwise successful artist.

Now, let’s lead by example.

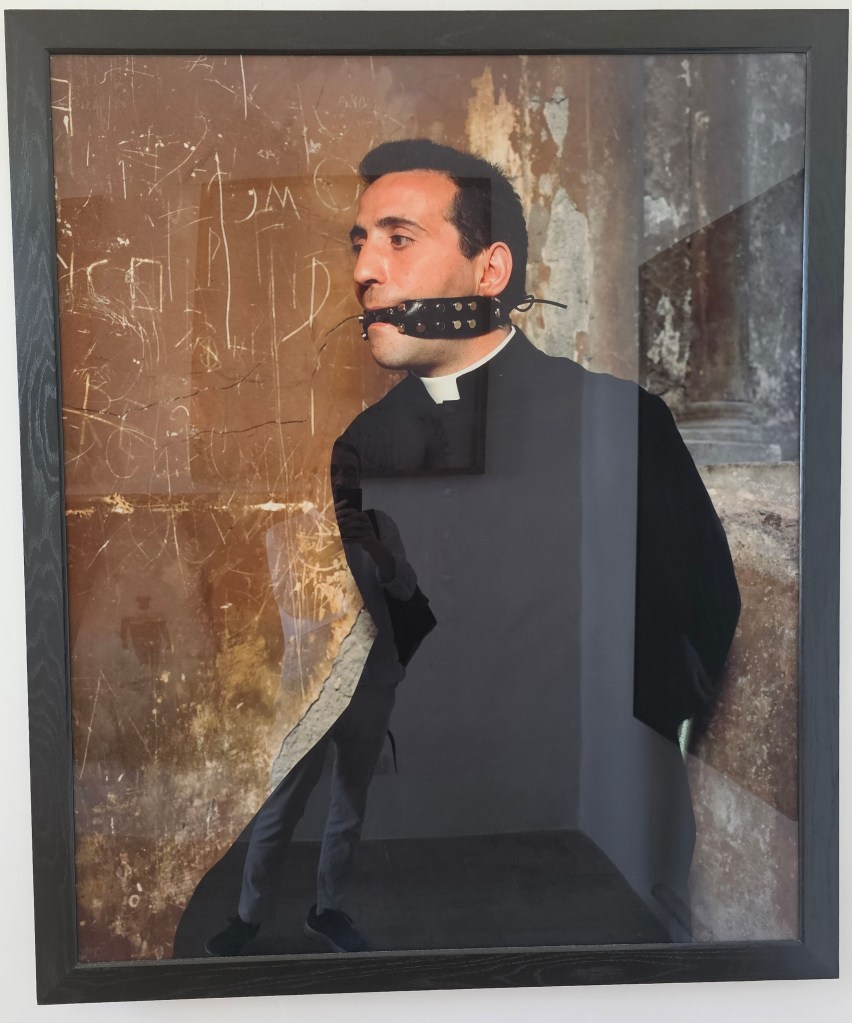

Andres Serrano challenges the viewer’s beliefs and convictions about relationships. He forces viewers to examine their reactions to his images. He puts his viewers on the path of discovering what causes their awkwardness, shame or excitement, thus helping people understand and reinvent themselves. And if you don’t feel challenged enough, google up the whole of Serrano’s series “The History of Sex” (More about Serrano here).

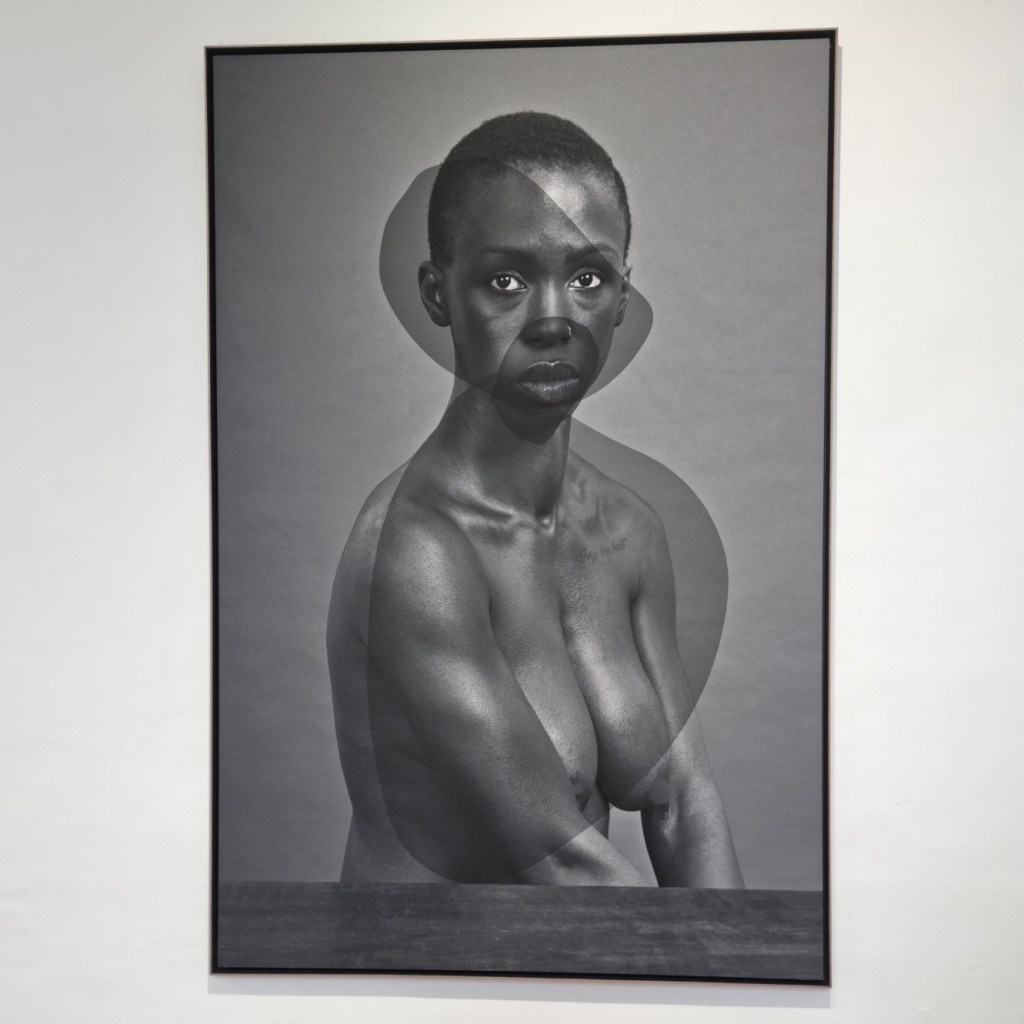

Another example is the work of Matteo Basile:

Masculine arms, gorgeous breasts, the sculpted body, the eyes of a fighter. She wants to tell you her story. It is a story of her battle, which is far from over. She looks at you, wondering if you are worthy of hearing it. Are you compassionate enough to listen, to see a human being within? And suddenly, the photograph is not about her – it is about you, the viewer.

What makes a staged photo great?

It is easier to think of it backwards. A truly awful staged photo is easily identifiable. It would be – almost entirely – about the mastery of the photographer, about showcasing their skill of setting light or playing with the shadows, of their flattery to the subject, be it a collection of objects or a sitter, and it would have quite a few unnecessary objects or details.

A not-so-bad staged photograph would tell a story. The problem here is that even if you get the story, you’d still ask yourself, why would anyone want to go to such extreme effort to tell you something that could be shown or said much easier and more efficiently? A not-so-bad staged photo leaves you somewhat disappointed – more often than not, it wastes your time.

A great staged photograph makes the viewer create a story – within the borders of the artist’s way of seeing the world. Even if you don’t agree with the artist on everything, this is never time lost; it is wisdom gained.

STAGED BUT PRESENTED AS UNSTAGED

Photos that are “staged but presented as unstaged” are a minefield. They are, by their nature, a cheat. If viewers begin to suspect the photographer cheated, they start hating the photographer’s work. If such a photo is done well, no one can assert whether it was staged – so it gets hung down in the limbo between the staged and unstaged.

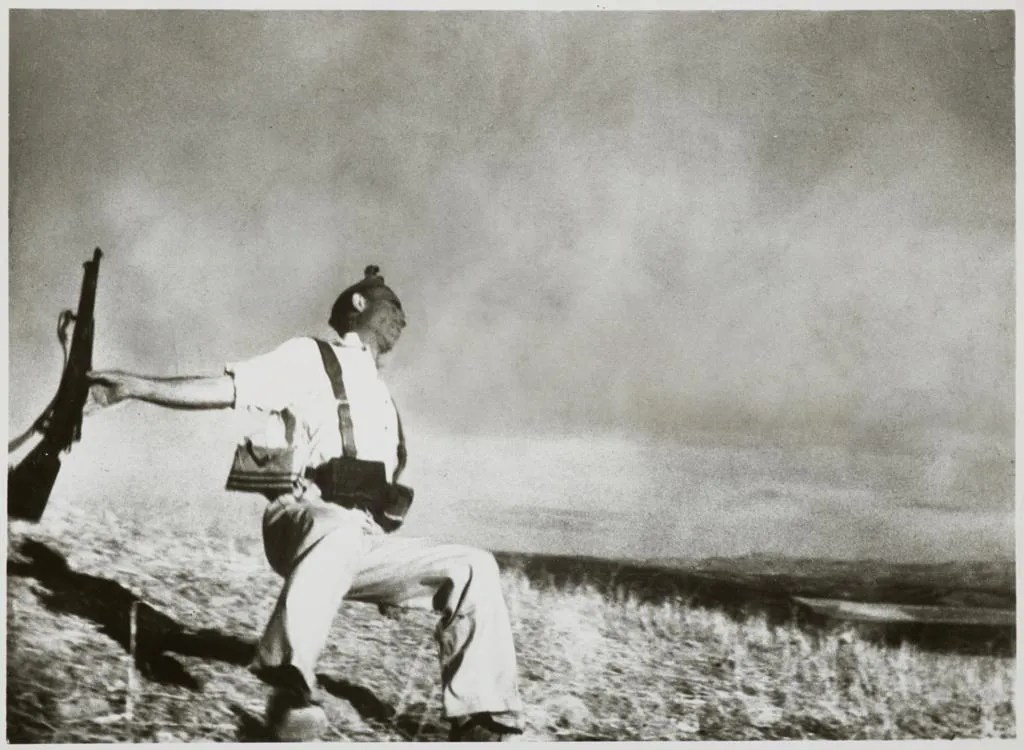

One of the most famous examples of these hung-in-limbo photographs is Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier (1938).

When it was presented, it was claimed to be a “hunting trophy”, the greatest image to capture the moment between life and death. Since then, it has been proven to be a staged proto. And yet, this work doesn’t enter my fine-art catalogue because it was initially presented as photojournalism and not fine art.

Just as with any great fiction book, in a seemingly staged photo, you’d have no unnecessary characters or details taking the viewer or reader’s attention away from the plot line.

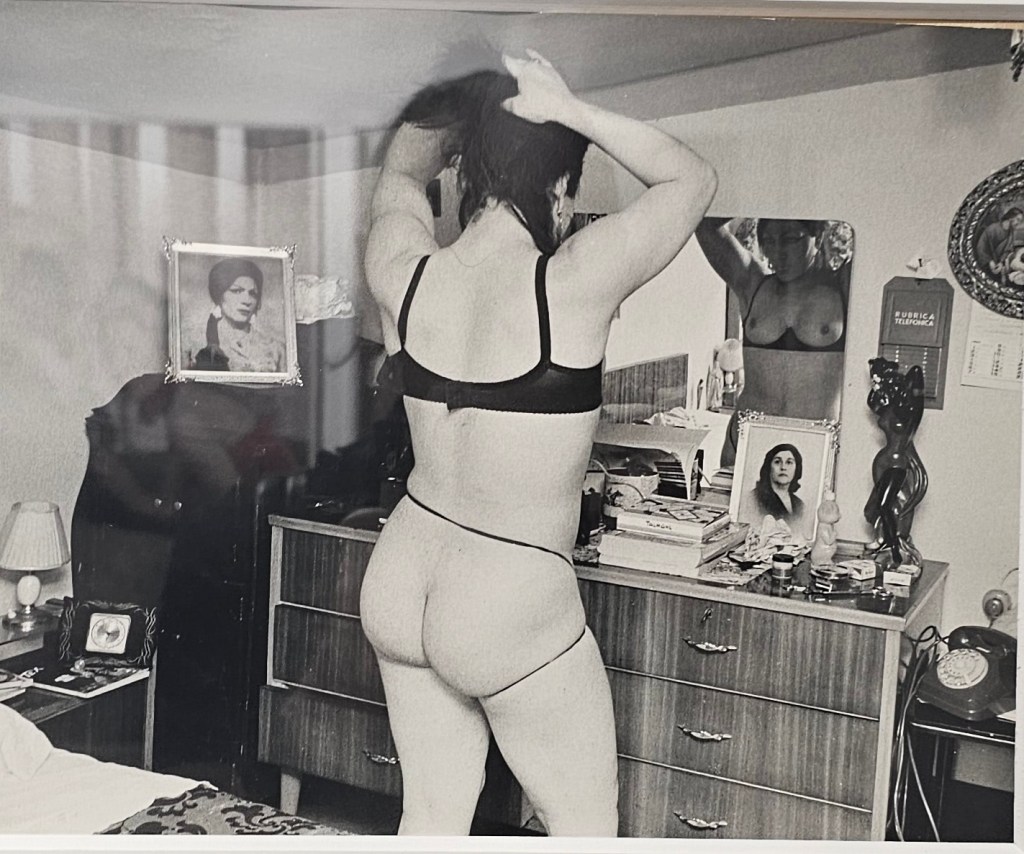

Here is a good example, I suspect (because I can’t be sure the photo was staged).

To explain the story in this photograph, I numbered the elements I will discuss now.

It is Italy in the 1970s. The woman is posing in front of and watching herself in the mirror, trying the pose of the statuette on the top of the chest of drawers (1). Society is OK with people putting this kind of bourgeois art on their shelves but doesn’t approve of women presenting themselves in this way. Still, she wants to show and understand her own beauty. Self-awareness is in her own eyes – she is studying herself. Her “exhibitionism” is the eyes of a woman of her age (maybe it is even her own portrait) (2). That woman watches you, the viewer, recording and studying your reaction to the model’s body. The older lady in the photo below the mirror (3) – the model’s mother? – us looking up at the model without much appreciation – it is the judgement of society, and I guess the average viewer back in the 1960s would furrow their brows in disapproval. By the bed, there is a cowboy comic book (4), hugely popular in Italy back then. The model in the photo is definitely past her teenage prime, but her soul, locked away in a cramped Genoese flat, wants to fly into the strong arms of a prince in shining armour. It is the same soul that is guarded by the Virgin on the other side of the bed (5). The lingerie on the model is obviously of a sexual nature. Is she expecting some cowboy now, with whom she would be making love under the watchful gaze of the Madonna? Or is she just dreaming about one, having put on this sexy piece to raise the sexual temperature on the inside? We can’t know this. What we can learn from this scene is that our beautiful model is tormented by internal conflicts, torn between her wants, fears and societal norms. And don’t forget about Dad and related issues – there is a Xmas picture on the wall with St.Joseph (6), conveniently cut off his family. What would he say, were he present or alive?

Though this photo may look chaotic, it is anything but. The story it tells is about the multi-dimensional generational conflict in Italian society of the 1970s. I still wonder about the symbolism of all the other elements in the picture, but I am grateful to the photographer who helped me to better understand Italy and Italians or even emotionally connect with the not-so-recent history of the country.

A different type of this staged-but-unstaged photography is here, in John Pepper’s photo from his Bathhouses series. It is borderline between unstaged and staged.

It is obviously at least semi-staged because the photographer (male) was invading the female space and had to ask permission. But heat, steam, diving in an ice hole and back to the steamy log house – it all makes one stop caring about a guy quietly sitting with his camera in the corner who, I am sure, having staged the occasion, didn’t try to stage the photo itself.

What I see here is the idea of rebirth, which is a big part of bathing rituals in many cultures. It is the legs that make you realise that a young woman has just been reborn in this, let’s admit it, not-so-young body. And it is not just age – it comes with all the carefree dreams and hopes. This photo tells a simple story. But its beauty is that the renewal feeling in it is contagious. In short, you can travel to, say, Norway, go to a bathhouse, and endure hours of torturing yourself to finally realise that all is not lost, or you can spend a minute looking – or rather watching – this image.

Much of Nan Goldin’s work falls into this “staged occasion – unstaged take” category, too:

A great “staged-but-unstaged” photo gives the viewer more freedom than a staged one. A staged photo is the artist’s demand for you to work. I’ve invested a lot of work into it trying to get my message or emotion across, says the artist; now it is your turn to understand what it was I wanted to do. The “staged-but-unstaged” approach gives you the freedom to build a narrative that is relevant exclusively to you. Beware of cheats, though. The ones that stage a photo and position it as “unstaged” with the sole purpose of making you believe it was a lucky chance. These artists take your freedom. They are the worst.

To sum up – though I love finding and enjoying great photos (as does anyone, I guess), I also have this categorisation system that helps me save time on bad ones. Feel free to use it.

Useful Links:

https://www.georgetatge.com/

http://johnrpepper.it/

https://www.giampaoloabbondio.com/

Thanks for this beautiful article. Above all because I always understood little about photography and now I can appreciate it better.

Si j e devais en choisir une seule ce serait ” The Falling Sodier ” car malheureusement encore d’actualité et le monde est toujours aussi noir !

Brilliant piece and an honour to be included. Thank you!

John R. Pepper