Imagine yourself a teenager of 13 years, who finds himself in the company of three of the greatest artists of your time. What would you learn from them? What would become of you?

As we progressed on our tour of the San Zeno Basilica of Verona (Part I and Part II), I promised to take you to Andrea Mantegna’s masterpiece of 1456, but to appreciate it, we need to step back in time for another 200 years.

Our first stop is 1222, when a group of students and teachers of the oldest European university in Bologna decided to plot their own path in science and set off to Padua, where they established a new campus. They valued freedom of expression above anything else, and Bologna had proven to be a place too stuffy for their liking.

Freedom of thought shaped their new motto, which in English would be “Liberty of Padua, universally and for all”.

The new university became the boiling pot of ideas and innovation, with the alumni including Copernicus (the father of astronomy), Andreas Vesalius (the father of anatomy), and Casanova (the father of adultery). Galileo Galilei held the math chair there for almost 20 years.

Giotto came to Padua in less than a hundred years and frescoed the Scrovegni Chapel (the iconic Kiss of Judas is there).

So, two hundred years before the year that we are interested in (1444), the university had become a catalyst of innovation for the whole of Northern Italy, with Padua at the centre. Much of that innovation depended on excavation, for the leading trend then was a theory that the more the antique past was understood, the more the present could reveal about the future.

Not surprisingly, the leading art studio in Padua in 1444 belonged to a 50-year-old artist, averagely skilled in art but very successful as an antiquarian. He collected and sold antique objects, sculptures, and manuscripts. His workshop had 137 students endlessly copying Roman designs (especially heavy fruit garlands) when not labouring on client orders. As a good businessman, this average artist was wise enough to always be on the lookout for talent. He loved passing the work of his gifted students as his own.

That was how he found Andrea Mantegna and even adopted him as his son (not to pay for Andrea’s work, of course). I wonder if Damien Hirst has ever entertained a similar idea.

Andrea Mantegna was 13 at the time.

1444 was the year when three most prominent masters of the time came to Padua. First, they were interested in Paduan collections of excavated classical past, and second, Padua encouraged experimentation and what today is called “the sacred right of freedom of expression.”

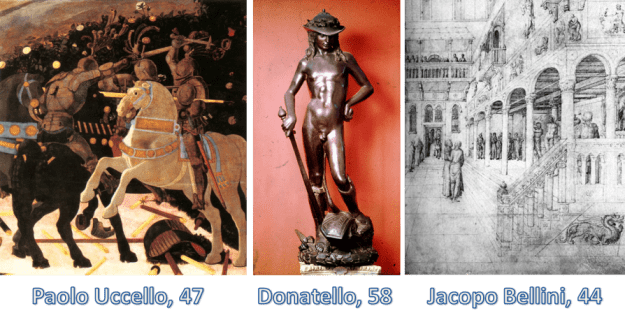

The three gurus were Paolo Uccello, Donatello, and Jacopo Bellini:

Donatello and Uccello were friends since apprenticeship times with Lorenzo Ghiberti (who made the gates of Florentine Baptisterium and had seriously pissed off Brunelleschi by winning the pitch). When a local cathedral landed a massive order to Donatello, he convinced his friend to join him.

Jacopo Bellini was the single most prominent artist from Venice. Rich and flamboyant, with a large household, he moved 30 miles away from the far more comfortable Venice to Padua because it was still part of the Venetian republic but had good schools, universities, and cheaper rents. Kids have always been changing their parents’ priorities, haven’t they?

Uccello innovated foreshortening and invented almost cinematographic dynamism in a perfectly still painting. He had studied perspective with a mathematical genius who was also the biographer of Brunelleschi, but he was not interested in perspective itself. He was interested in how he could twist perspective to accommodate a bigger world in his paintings than the one limited by the frame of the painting and pre-defined by a single converging point.

Jacopo Bellini worked together with Leon Battista Alberti for a few years before he came to Padua. Alberti wrote the first book on perspective for artists and published it nine years before the events I am describing. As you can see from Bellini’s drawing above, Alberti’s knowledge rubbed off: Jacopo got deeply interested in complex perspective compositions. Unlike Paolo Uccello, Bellini was more interested in how new colour combinations he invented could combine with perspective solutions than in the perspective itself.

And, certainly, there was an exchange of ideas going on between the artists:

Donatello adopted the perspective inventions of Brunelleschi, his friend and mentor, in sculpture. He broke up with the Gothic past, paving the way for the realism of the Renaissance with the Man in the centre. It can be best seen when you compare his work to his contemporaries. I will show you the difference, easily illustrated by the bas-reliefs in Siena’s Baptisterium on which Donatello worked together with his former teacher, Ghiberti.

This is the Siena Baptisterium, with its Baptismal Font on a podium (I had to crouch so much to take accurate shots that some tourists were taking pictures of me):

Let’s take the side made by Ghiberti:

This is the Baptism of Christ by Lorenzo Ghiberti. John the Baptist pours water over Christ’s head, the Holy Spirit descends from Heaven, spectators look at each other in amazement, and angels rejoice and flutter their wings. A good film director would probably show the trembling hands of St.John, who is accomplishing his prophetic mission, the exalted face of Christ, spectators watching the miracle and clasping their hands in amazement… Yet, Ghiberti’s work is static and flat. All the characters in this drama exist on a single plane, with depth represented by angels’ reliefs thinning out…towards the non-existent horizon? Or towards Heaven? And why would they be flying in this strange formation?

And this is Donatello’s panel, the Beheading of John the Baptist:

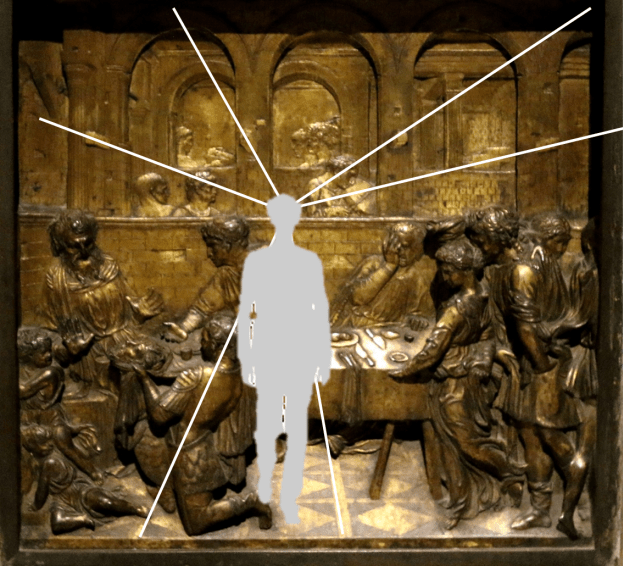

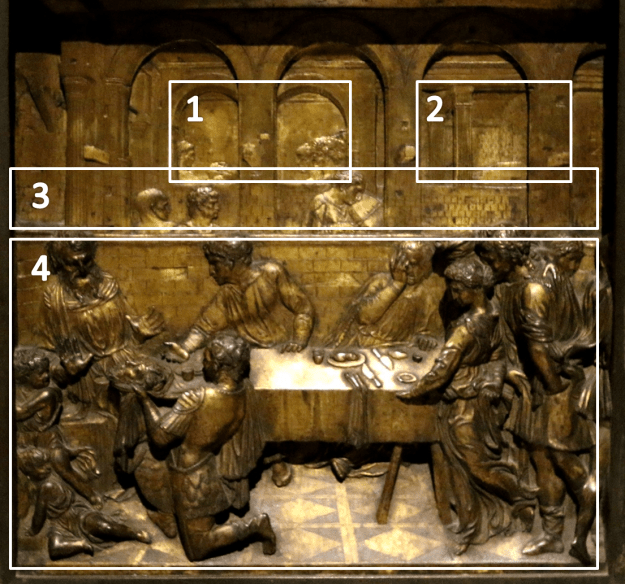

It is a short movie frozen in bronze. Each scene has its own perspective or camera angle: convergence points are ever slightly different from one scene to the next, but not so different as to make the observer’s head spin like from watching an Escher’s etching. There are four scenes in it:

In Scene 1, the executioner shows John’s severed head to three servants who brought a plate on which it is to be presented to Herod. The Deed is Done.

Scene 2. It has no people in it. It is a close-up view of the stairs that lead up from the dungeon where John the Baptist was executed. It is the connection to the world of life, celebrations, dancing, and earthly love.

Scene 3 This scene shows the executioner and a servant carrying the head through a gallery with musicians playing a merry tune to which Salome, Herod’s adopted daughter, who asked for John’s head on the insistence of her mother, is dancing below.

Scene 4 Finally, there is the climax, when the head is presented to Herod. Most guests are terrified, as if a hand grenade just went off, but Salome doesn’t break her dance as if oblivious to the tragedy unfolding in front of her.

The construction of perspective in Scene 4 is deliberate, guiding the observer, YOU, to a specific vantage point: standing closer to Herod, away from the alluring Salome, witnessing the head being presented to the king.

That’s how different Donatello was from his contemporaries. Now that we know he was a genius (and not just believe in it because someone said so), we can go back to our teenage Andrea Mantegna to see how the three artists inspired and shaped him. There are only two things to see before we flip the page over.

It was in the year 1444, in Padua, that Donatello was engrossed in crafting the high altar for the Basilica of St. Antony:

Remember the proportions of this imposing edifice.

One of Donatello’s assistants produced this altar, also in Padua:

You didn’t expect this photo here, I believe.

Why is this an exciting picture? Because we know that no one ventured on the moon before. Now, Renaissance art is very much like this: going where no one could or dared to go.

We need to see some of the best examples of altarpieces produced before Mantegna to understand what was his boot print in art.

Beato Angelico painted this altarpiece sometime around 1437-1447, and it is, perhaps, one of the best examples of this painting genre that young Mantegna might have been exposed to.

The upper part is very gothic, with the saints parading their best robes against the heavenly (that adjective also covers the cost of material) golden background.

The lower part, the so-called predella, looks quite innovative and “modern”: no gold leaf, clever perspective, and complex compositions. It seems two different artists worked on this altarpiece.

It resembles a Gothic basilica, and, in fact, it was meant to do just that. The carved frame was a portal to the celestial world of saints and martyrs, which is why the openings resemble windows or doors.

Such was the tradition before Mantegna.

Twelve years after the encounter with the three geniuses, Mantegna comes up with this altarpiece for San Zeno Basilica, where he unites painting and sculpture (he is believed to be the author of the sculptural wooden frame as well):

This wiki image doesn’t begin to convey the beauty of the work. The colours, for one thing, are totally off-key. Quality images of the San Zeno altarpiece are rare. It is one of the worst-exhibited masterpieces in the world.

The best view you can get is this:

You can’t approach it. Light from the windows gets reflected on glossy tempera, preventing a good view of large parts of it. Instead, you are given a replica of a 12th-century stone altar to enjoy. Thank you very much, guys. Beautiful flowers. I had to use a telescopic lens (no tripod is allowed) to see it for myself.

This is the best work of art in Verona, and it is inaccessible. Shame.

We’d have to work with what’s available then.

The real colours:

In my next post, I will show how this altarpiece represents not just the melting pot of ideas that Mantegna had become, but also his innovative genius – and he was not even 30 when he completed it. I am sure you picked up the general idea already, but I’ll just have it illustrated.

I always liked Donatello’s David because the style reminds me of Hellenistic era sculpture which makes it an interesting comparison to Michelangelo’s more Greco-Roman David.

You are very right, I guess. Donatello’s David was about the dawn of Florentine republic, while Michelangelo’s one stood for its sunset, somewhat mirroring the relationship between the Hellenistic and Roman art )

Beautiful. But I am particularly blown away by the ceiling frescoes on p. 2.

PS – father of adultery? come on, too much credit 😉 but probably father to 1000 illegitimate kids!

It may take a few hours, studying the frescoes. I made hundreds of photos there, and I only wish I had more time )

Reblogged this on VINTAGE STUDENT.

This post was an absolute joy to read! Thank you!

Thank you for saying it – that’s the kind of posts that require readers to work a bit, and I have to put in a lot of effort into making the story involving. Still, only those who are genuinely interested in art are tough enough to go through all the pages )

Your post is opening a door for understanding and that´s always fascinating.

Thank you! Thank you indeed!