Great artists steal, poor artists borrow. Picasso was first to say it, but it had been done long before him.

How to steal ideas from five other artists and still produce something they couldn’t have made, something truly innovative?

This is the final part on Mantegna’s masterpiece. Easy reading, if you’ve read Part III: you’ll intuitively understand what was “stolen” from whom.

Mantegna stole the general idea from Donatello’s assistant, who made this sculptural altar. It includes the overall shape and the way the composition is organised. The stone altarpiece is far from perfect:

- The space in which the Virgin is seated is flat: there’s no volume.

- Proportions don’t seem right: the whole structure looks heavy as if weighed down by decorations and angels on top of it, which also draws attention away from the main composition in the centre.

Mantegna then borrowed Donatello’s own ideas of decoration, and, most importantly, proportions:

He appropriated the architectural ideas of his future father-in-law, Jacopo Bellini, to create celestial space for the Virgin and saints:

And if I remove the woodwork, you’ll see it much better:

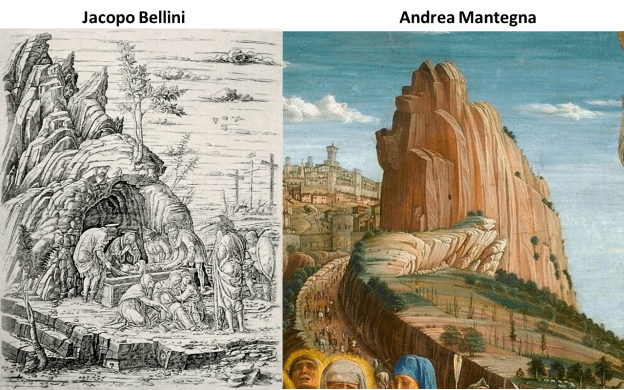

He also picked up landscaping ideas from the old man, clearly visible in the predella (and the cloud shapes as well):

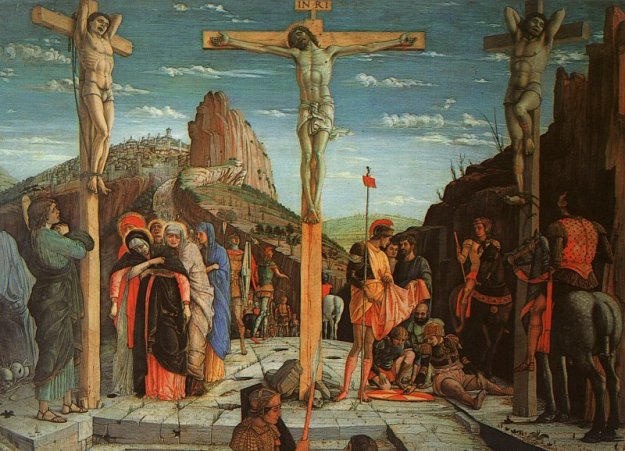

The rhythm and movement are both the influences of Uccello and Bellini, clearly visible in the Crucifixion predella. I am putting Uccello and Bellini together so that you can appreciate the extent to which Mantegna’s future father-in-law was fascinated by the Uccello’s visual trick when the spears denote lines of action, lines of sight, and groups of people in a complex composition:

Mantegna puts the observer in front of Christ, and inside the crowd, but not above it. He then lowers the horizon line and uses landscape to add emotion and significance to the scene. In Bellini’s work (above) the crucifixion looks like a regular execution outside the town walls. Mantegna, having fewer people(!) at the foreground, makes it an epic moment with crowds of spectators, showing them as “dots” on the road to Jerusalem:

Indeed, the show is over; there’s no point in staying, unless you’re a relative of the executed or a soldier whose pay has been so much overdue he doesn’t have money to buy a new pair of sandals and has to gamble on the meagre possessions of the crucified.

Who could blame this guard, seeing the torn soles of his shoes?

The love for anything and everything classical and antique was indoctrinated in Mantegna by his first teacher and adopted father, Squarcione. And even though Mantegna sued Squarcione to rid himself of his care, he remained passionate about all things classic. Mantegna could draw legionnaire’s armour with such “archaeological” accuracy that hadn’t been seen before and wouldn’t be seen for a hundred years after him.

At this point, you might wonder if Mantegna was borrowing ideas and simply improving them. What innovation made his stealing worthwhile?

In Part III, I mentioned that altarpieces were meant to be portals to the celestial world, with individual saints often portrayed in “windows” or “doors” opening up to Heavens:

Mantegna gives us not a window to the Heavens, but a 3D portal, 500+ years before the Stargate franchise came up with their portal to other worlds.

He joined the Heavens and the mortal observer by placing the real half of columns in front of the painted ones, and hanging the fruit garlands between the two. I masked the woodwork again to highlight the trick:

Thus, Mantegna fused together painting, sculpture, architecture, and history (and one may also add archaeology) in a single artwork. A 3D experience of the 15th century.

I can go on and on, talking about the way the saints communicate with each other, or how Mantegna changed perspective (a little bit) to bring the saints closer to the observer. Compare his preparatory drawing with the correct perspective to the final execution:

Are all these visual inventions and tricks important? These subtleties may be lost on a group of tourists herded by a stern guide off the bus, into the Cathedral, and on the bus again a short while later. However, it’s crucial to remember that this is not how people were used to watching this art. They would see it day after day, mass after mass, often from different angles, and they would keep discovering nuances, details, emotions, themselves, the Virgin, the saints, and the Heavens.

I long for a gallery experience that allows visitors to borrow foldable chairs, creating a more relaxed and personal connection with the art.

Before I part with this altarpiece, there’s just one “parallel” you may enjoy:

Now you can understand how much I envy these people:

Come visit Verona. Renaissance art is never boring, if you know its story.

Another great post on Art History. I like the comparisons and interpretations. Very good.

Thank you! Too many people take art of the past as great by default, and lose interest in it, without bothering to understand whether and why it is great ) Hopefully, I can remedy it, from time to time!

Mantegna’s colors pop out so vividly. The panels give such a quality 3D perspective that there’s no way he could have achieved it without building off of what Bellini achieved with perspective. Do you plan to write on the van Eycks? Their altars are amongst my favorites.

Thank you for the tip: I need to look at the overall artistic developments in Europe more, not just Italy, I guess!