What I love about Italy is that it is a patchwork of different epochs, styles, and cultures, which are often quite opposing and contradictory but peacefully co-existing. The symbol of Yin & Yan should have been invented in Italy.

Take Forte dei Marmi, a paradise spot for millionaires, their kids, nannies, fitness instructors, and cocaine suppliers. It is white (no black people except peddlers of fake LV bags), posh, and clean as the bottom of a cat with obsessive compulsive disorder centered on the cleanness of its bottom. I know some people believe cats are normally born with it, so imagine it to be double the norm.

Its boutiques stay open until midnight absorbing the apre-dinner crowd wearing a relaxed mix of casual attire and expensive diamonds. If you cringe at “expensive diamonds”, trust me, it is not a tautology in Forte. There are diamonds, and there are expensive diamonds; and the latter are noticeably different to the former in size and quantity. It’s the kind of diamonds that make you murmur, “It must be a fake” when you see them except that they are not. Don’t worry, though, Forte is a safe place. Of course, once a year a Rolex gets forced off the manicured hand of its wearer or a villa is robbed while its residents are put to sleep by some soporific gas, but given the number of Swiss watches and luxury homes in the area, it’s a small price the rich have to pay for being open-minded about the inclusion of the more unstable East European countries into the EU. Ultimately, the Forte’s rich would either earn their money back off those nations or steal it from their own. Fair’s fair. And yes, the word “earn” in Forte has a very different meaning to the same verb in, say, neigbouring Livorno.

In Livorno, the opposite of Forte, you don’t wear an expensive watch, because Livorno’s large immigrant community keeps a close watch on you at all times. A non-prejudiced tourist may take those stares for a sincere wish to help with city navigation, but the inner genius of intuition whispers that it is better to stay inconspicuous. Show off is never welcomed by socialists, and there are many of them in Livorno, for it is a place that has been holding socialist ideas close and dear to its heart ever since the communist party was founded there almost a hundred years ago.

Not that Livorno’s infatuation with communism has done anything good for the city. It is not a prosperous community, not very clean, and you won’t be able to pop into a Hermes store after your mid-night MacDonald’s dinner. While activists are busy leaving communist graffiti on the walls of public buildings, its churches crumble, its businesses twinkle out of existence, its palaces decay and peel off as if cursed by their capitalist ex-owners, with the net effect of activists’ leaving even more communist graffiti.

There is still a lot of charm in this fading star of a town, bombed flat during the WWII, and rebuilt by post-war architects who will not be celebrated in any foreseeable future for the beauty of their creations:

Do I like Livorno? Well, you might have already guessed that I hate Forte dei Marmi, the modern vanity fair for corrupt politicians, oligarchs (mostly Russian and the former ex-USSR, of course) and their menials. Forte is not a place where money creates anything good or anything at all. I am allergic to it so much I never take pictures there, and leave the town as soon as the annual obligatory dinner with friends who happen to like Forte is over. But, if you are interested, here are some good links 1, 2.

My dislike for Forte (let’s say it is Yin) doesn’t make me a big fan of Livorno (which is Yan), though. I am a firm believer that socialism is bad for you. If you contract socialism, you need to be isolated at the first signs of the disease . If you happen to be a socialist, please don’t even think about dissuading me: I’ve lived a half of my life under this “just” social order. Very few things make me happier than hitting a communist on the head with a tome of Das Kapital by Karl Marx.

Yet, Livorno is Italy, and Forte is not. It can be easily proven by arts and culture. In Forte, art galleries are outlets for gaudy po(o)p art that discredits the country’s culture and heritage. In Livorno, good art can still be found, and to see it we’ll go to Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori.

It is housed in a building that doesn’t strike you as a museum (Yan). It looks abandoned, like a homeless person slumped against the wall, when you are not sure if he is asleep temporarily or eternally.

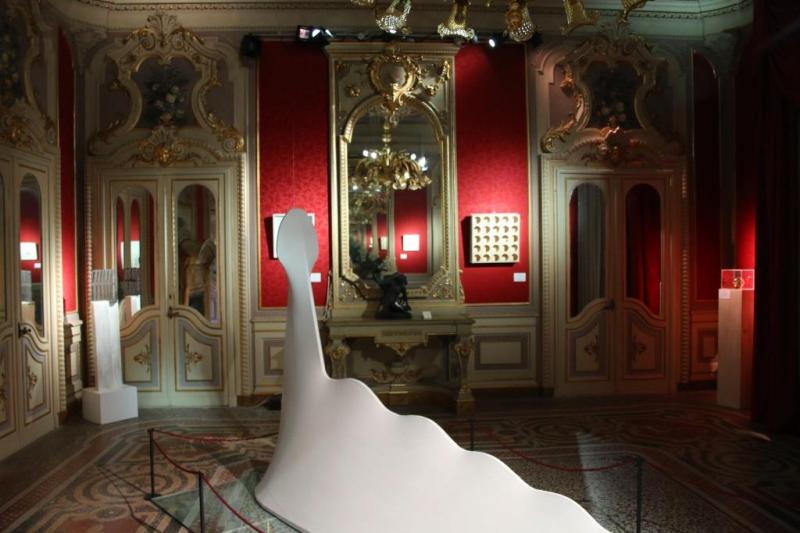

As you enter it, you are hit by the past glory of the prosperous capitalistic Livorno (Yin) mixed with the scent of imaginary mothballs (there are no real mothballs there, but you still can feel the smell).

Putting contemporary art in a historic setting is one of the oldest curatorial tricks to show that creative life is still pretty much alive and kicking, and it is also a kind of Yin&Yan.

Yet, when I was there, I had a feeling Livorno’s contemporary art has lost the vitality required to make something beyond eye-pleasing decorative pieces. Perhaps, it was just too hot outside, and I missed the breakthrough kind of art.

Fortunately, there are a few great artworks well worth a detour, as they say in tourist guides.

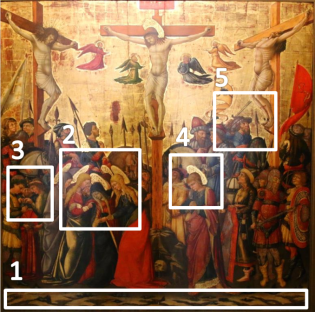

This painting by Neri di Bicci is a good example of the decorative branch of the Renaissance that ultimately peaked out at Botticelli (as opposed to the humanistic chapter of Masaccio and Michelangelo).

If you have been to the Medici Palace in Florence, and visited the Magi chapel frescoed by Benozzo Gozzoli, you’d understand what I mean.

Why is it an interesting piece of Renaissance art?

It is a multi-figure composition where everyone is visible and has a role. Bicci shows a broad range of emotional states: sorrow, contrition, disinterest, curiosity, disapproval, approval, etc. You can play a game of mapping emotions against each character or group of characters in this painting and see if you and your friends are good at recognising emotions.

I will focus at a few elements in this painting, but before that notice how this representation of Christ’s last passion is soaked in passionate red. It was an expensive colour at the time, by the way.

1. The land

1. The land

It is a very narrow strip of land that is painted in such a way that it creates the feeling of a flat on which the whole composition is built, and takes you inside the painting, without directing you to anything particular at all. Clever.

2. The mourners

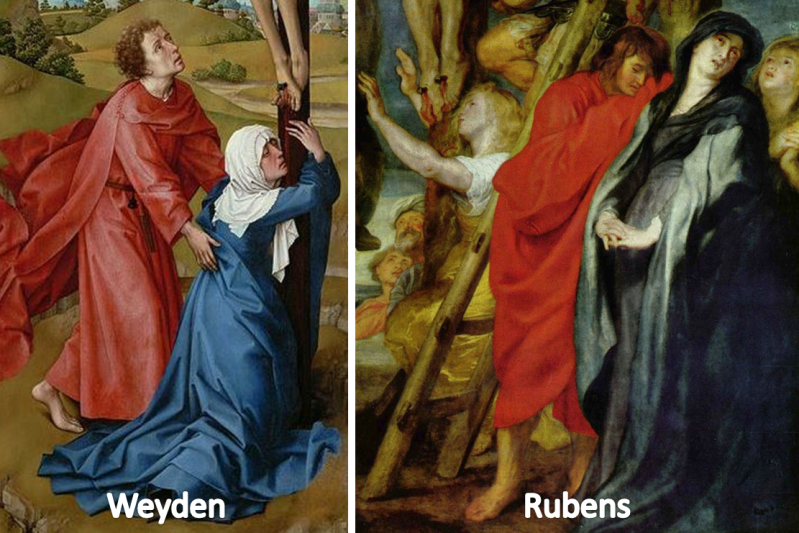

The beauty here is not in the suffering of collapsing Mary (that was not an innovation even then), but the attitude of the saintly ladies who support her. They don’t have time to cry or agonise over the Crucifixion, which has already happened; they have a more immediate and pressing task at hand. They don’t look up at Christ: that can wait. They care about his mother. And that is very true, much more so than the scenes painted with greater mastery by Rogier van der Weyden about the same time, or by Rubens much later.

When an old woman collapses one has to look down to support her, and even if the old woman doesn’t collapse (but you know she’s suffering a lot) you don’t lean on her while walking at the same time.

3. Gamblers

This is an important scene to which attention is drawn specifically by the hand and finger of a mounted man above them. Roman soldiers are drawing straws for Christ’s possessions.

They stand next to the group of mourners but seem oblivious of the dramatic events taking place around them. They are fully engrossed in their get-rich-quick game. Of course it was meant to be a moral lesson (with the point driven even further by having the three ages of man in this group), but… yeah, men are like that. The whole world would be collapsing around them, and they’d keep thumping through news on their iPads.

4. St.John

Yes! Women tend women, men think of bigger issues. One man looks up, St.John looks down, and the observer looks up and down, thinking of Christ’s sacrifice and his own future lifestyle choices. St.John didn’t come out well on my camera, but the strained concentration on his face can still be seen, that together with his clasped hands tell you a lot about the inner pain inside the man.

5. Torturer

This man is the most ugly character of all the Roman soldiers. He enjoys inflicting unnecessary pain on a powerless condemned brigand as a cruel boy pinching wings off a fly to see how it’d wriggle, unable to take off. His helmet is splashed with blood that he doesn’t seem to notice: the suffering of the crucified man is holding his undivided attention.

You probably won’t shake the man’s hand if you met him socially, but…look inside your own mind and remember if you have ever inflicted unnecessary pain on someone. The point is not to brand the man as a horrible brute.

This Crucifixion is an interesting piece, but we have to keep going, and climb an amazing staircase to the first floor with 19th century paintings by Giovanni Fattori there.

And that’s when the tortured babies come into play, the total Yan to Neri di Bicci’s Yin.

Stay tuned for the horror, I’ll post it soon.

me gusta pongan mas cosas

Reblogged this on VINTAGE STUDENT.

Those paintings are full of thought and meaning. You bring it out well.

Leslie

Thank you, Leslie!

Very interesting post. Many thanks for it!

Thank you for reading all these travel notes!)

Reblogged this on Concierge Librarian.