How many writers got famous long after they had died? How many manuscripts have been discovered by literature enthusiasts to be published in all their new-found post-mortem glory?

I don’t know, actually, but I am sure the number is infinitely small in comparison with the crowd of painters who became icons after their death.

There’s logic to it.

There are so many painters around, even good and great ones, that it is easier to find an artist to do a portrait than a reliable workman to paint a house. When people learn I write about art, they often start throwing artists’ names at me, expecting a reaction. No, I don’t know all the painters. I probably know some 2% of good ones, and even that is an awful lot against the market average. The sad fact of life is that painters don’t live long enough to get noticed, but, unlike manuscripts, paintings often acquire a life of their own after their creator ceases to exist.

Thus, the path to greatness for painters is nowhere near the writers’ road to the same destination. A painter (or rather his heritage) needs to be “tested by time” (just like the paint job on a house) to become properly recognised by Wikipedia or, ultimately, forgotten even by Google.

Sculptors are in-between writers and painters for the simple reason of cost. A painter can go on painting for years working as a bus driver. A sculptor needs a lot more money than a bus driver’s wage to keep up sculpting.

There are a few lucky exceptions, of course. Fernando Botero, a Colombian painter and sculptor, is one of them.

I am sure you know Botero even if you don’t know the name. You must have seen some of his fat birds, animals, or plump women.

I guess I know how his sculptures work.

Remember Archimedes principle? When he was taking a bath and realised he could weigh an object by weighing water it displaces when submerged (with adjustment for the object and water’s density)?

Same thing here.

The giant sparrow is dropped in the mind of an observer like a ton of bricks in a backyard pool. It pushes out torrents of other thoughts, leaving you wondering “What the hell is this thing doing in my pool brain?!”. Once you’ve seen it, it can’t become unseen.

Is Botero’s art great beyond just its size? I am not sure. It definitely livens up the cityscape and makes up for a good meeting point. Some critics believe this itself is a Nobel-prize achievement.

Officially, of course, Botero is the greatest living artist in the whole of South America. He has won so many prizes, accolades, interviews, and commissions that Michelangelo would be shamed into hiding. And, as it often happens with people who become officially great, Botero has turned his creative eye (and I can’t stop seeing it as a bloated eyeball slowly rotating inside a huge eye socket inside a giant head) to the New Testament. You see, great people are attracted to other great people, and who’s greater than Christ?

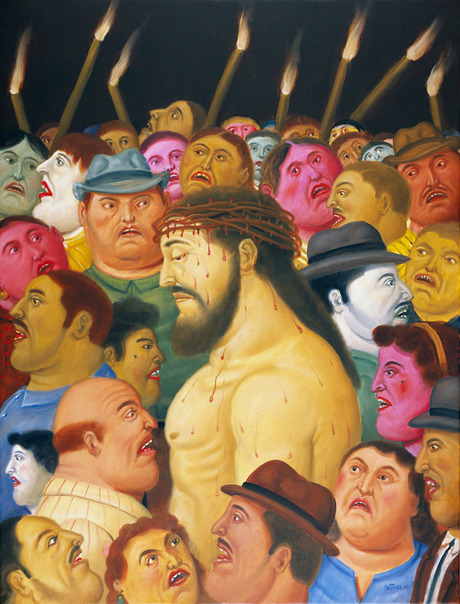

The creative result of this eye movement is a collection of several dozen paintings on Christ’s passions. It is titled “Via Crucis”, and I had a chance to see it in Palermo a few weeks ago.

My great friend John Pepper (who is also my only friend with a Wikipedia entry) took a few photographs of me watching the paintings. He insists my method needs to be exposed.

Yes, I watch paintings like an HP scanner, but without the humming noise. I am sure Botero did not intend his works to be watched like this, because similarly to his sculptures, he drops his characters into your mind like a bomber aircraft on a raid. The pillbox of your brain is supposed to be hammered by massive visual explosions, rather than fall victim to the creative bullets of fine lines and inventive brushwork. But there I am, breaking the rules, watching paintings in slow motion.

I do it, because the way a painter works on a line or a border of two colour fields, etc. can speak volumes about the artist’s intentions. i map a painting by the amount of effort invested into its different parts and it helps me understand what the artist thought was important, and when everything is put together, I can come up with a hypothesis of why the artist thought it important. And of course this scanning is just one of the tools I use.

Scanning Botero is boring. His effort is distributed evenly across the canvas. This is exactly what you see in Turkish carpets, woven with mathematical precision by women who gradually go blind while their husbands gradually go richer selling them. When I learned the story behind handmade Turkish carpets, I vowed never to buy them.

Perhaps, you would expect sculpted paintings from a sculptor who made his name by the displacement of large volumes of air to stratosphere and beyond. Instead, they look like applications, or cut-outs pasted onto canvas with the finely shadowed borders between neighbouring colour fields that imply a few-millimetre distance between a figure and the background.

It’s not that Botero has invented this technique for the Crucifixion series. It is his trademark style. He “applies” his plump figures to the canvas’ flatness as if pasting a myth onto the fabric of today’s reality. It’s like dressing a doll in cut-out paper dresses.

Botero’s Christ, force-fed into obesity, roams empty streets of a modern town, stumbling, falling, being hit by an occasional police patrol, and being helped by a random bystander. He carries his cross around and seems to be utterly lost among the cubicles of sun-roasted houses. People’s clothes alternate between something ancient and very modern, creating the reality that si-fi writers define as a seam between two worlds.

If Botero wanted to say that Christ has somehow got lost in the time and space continuum, he succeeded. Many Christians would disagree, of course. Does this statement come as a revelation? Well, I guess not.

If Botero wanted to bring Christ to life in this way, revive Him as a mortal amongst mortals (note the absence of halos) I am not sure I am convinced. Yes, Botero uses colour conflicts to convey emotion. Yes, Botero’s compositions are sculpturally monumental even though they have no depth. Look at the two figures above. They are frozen in time as a bronze-cast twin pair of the prosecutor and the persecuted.

Yes, Botero is always unmistakably Botero. But frankly, I don’t need an oversized human figure shoved in my face to remember that Man can be a giant metaphorically, while being a fragile sack of muscle and bone at the same time. It’s a trite idea. Other people, painters, writers, and sculptors have trampled out this territory into wasteland. It would take more than just a replay of the good old New Testament theme to grow something on it.

And, speaking about the time test, after a few weeks, only two paintings seem to have stayed in my memory.

I remembered Jesus and the Crowd because it made me recall an installation I wrote about here. I find the installation, addressing the same issues, a way more interesting artwork than the painting.

In this installation you really get the feeling that Christ is present and you miss to meet Him, because you indeed have to walk past him. This makes your skin crawl, even if you are a third-generation atheist.

The other painting that has stuck in my mind like a nail is this image of, well, the nailing of Christ’s hand to the cross:

I find this painting highly symbolic. Christ’s hand is opened in a gesture of offering something (and we know what it was that He offered: a suggestion that being nice to each other may not be such a bad idea for a change). Yet, the “reply” comes in the form of a nail hammered into it. And the blood that comes out of the wound is not the usual smear or rivulet. It is a fountain in which Man can cleanse his soul through the Communion.

Now, that is clever. This is the first time the nailing was painted in a way that unites Man’s sinful existence and his path to salvation.

It is one small painting among dozens, but it alone makes the whole show worth visiting if it comes to your town. Perhaps, you’d find more of Botero that will pass the time stress-test.

I like the concept that if Christ were to come back today in our fast-moving, digital world and stand on the street to call people towards him, he would probably be considered a crazy religious manic by the people,if they stop long enough to listen to him. My question is: why does all of Botero’s art consist of obese people? Does he imagine that one doesn’t encounter the problem enough in daily life?

Well, Botero says he’s making them voluminous not fat, and that it is his trick to make them sensual. I think he simply found a formula to create images that, as I wrote in the post, stay in memory once you’ve seen them, and all the justifications and explanations have come later. He invented his own Human, populated his worlds with his Voluminous Humans, and whistles all the way to the bank while critics struggle to understand the deep meaning behind his transformation trick.

Reblogged this on VINTAGE STUDENT.

Interestingly my take on Botero’s ‘plump aesthetics’ is quite different. A plump Christ is a Christ that the very ordinary person, the burger who enjoys a ‘plump’ meal cooked by his plump wife in his stuffy home full of tchotchki – identifies with. The lean tormented Jesus is everything that our man is not, he is alien and screams “guilt!” to him. As weird as it may sound, I don’t see Botero’s huge figures as monumental, but as small, figuratively speaking. They are not Titans, they are clerks dragging an 8-6 existence in inconspicuous towns. Maybe because ‘monumental’ implies force, while plump – and I see them as plump – implies cushy, cosy. Huge soft toys. Same with his women – they are fleshy and curvy and as void of sex appeal as teddy bears. I take his art as kind of tongue in cheek. What do you think?

You see, plump figures appeared long before Via Crucis. It’s kind of his trademark style, but the plumpness of via Crucis series is different. Compared to Botero’s other works, his Christs is quite mulscular: And – come to think of it – Botero’s Abu Graib series is definitely not plump at all.

And – come to think of it – Botero’s Abu Graib series is definitely not plump at all.

Bystanders or ordinary folks are often shown as plump philistines

When I say “monumental” I think of how the composition of the main figures is organised in a painting. They are like full-scale or bigger-than-life sculptures, frozen in their movement. They don’t show movement, but stand a big monument to the movement’s consequences.

I think, Botero’s style might have emerged as a tongue-in-cheek response to the glamorous sexualisation of everything, or as a response to the lean lifestyles he witnessed in Colombia, and at some point it hit the nerve of the society tired of the sexual motivation in everything. But today, I believe, it is just “trademark style” with plumpness varied according to circumstance.

Botero’s paintings here remind me of Mad Magazine.

I tried to google the mag, but I still could get the idea of what it is about… Is it a comics mag?

It’s a satirical comic.

If you’re working on a device that can run Flash Player, you’ll find examples in the NYT here: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2008/03/28/arts/20080330_FOLD_IN_FEATURE.html

If not, here’s a single example: https://iamjealous.wordpress.com/2008/04/02/of-your-fold-in/

The artist of these fold-in-page images of the mag is Al Jafee.

OK, thank you! Now I get it )

Interesting religious interpretation. Some how a fat Christ doesn’t resonate.

Leslie

In a different dimension, or universe, Christ could well be fat, just like everyone else ) Perhaps, Botero comes from a different planet?

A leaner Christ does bring out the suffering he is suppose to have incurred.

Leslie

Great post. I would have loved to go to that art installation.

Thank you! ) Alas, as of today, it is only possible to read of it in this blog.

You should start humming.

Then, I fear, it will become an art performance, not just a regular watching process )

Or maybe like a mmmeditation? I might do the same myself, seems soothing.

What a lovely read!

Thank you – glad you enjoyed it!